CONSIDERATIONS FOR LONG-Used TREATMENT OPTIONS

THE USE OF ADEQUATE BCG HAS BEEN AN EFFECTIVE STRATEGY FOR THE TREATMENT OF HIGH-RISK NMIBC2

The FDA defines adequate BCG therapy as at least one of the following3

- At least 5 of 6 doses of an initial induction course plus at least 2 of 3 doses of maintenance therapy

- At least 5 of 6 doses of an initial induction course plus at least 2 of 6 doses of a second induction course

BCG efficacy data

- In a meta-analysis of 9 trials including 700 patients, ~70% of patients with carcinoma in situ (CIS) experienced complete response with BCG (varying regimens)2

BCG is an intravesical fluid therapy

- Intravesical instillations deliver therapy directly to the bladder, while limiting systemic exposure4,5

- Intravesical instillations rely on contact with the urothelium to ensure exposure to therapy4,5

- The dwell time of the intravesical fluid BCG is 2 hours, voiding early if necessary6,7

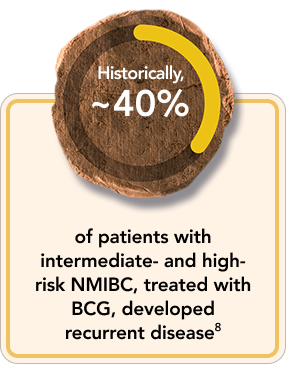

PATIENTS MAY EXPERIENCE DISEASE RECURRENCE DESPITE ADEQUATE BCG THERAPY

- Data are from a formal meta-analysis of 11 eligible studies conducted between 1987 and 2000 in 2,749 patients. CIS outcomes were only documented in 4 studies and the number of patients was too small for a formal analysis. Overall, the median follow-up was 26 months8

- In patients with HR-NMIBC with CIS, treated with adequate BCG, the 5-year recurrence-free survival has been reported to be ~25-80%9-11

- Based on data from 3 retrospective analyses: a multi-institutional review of 299 patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC treated at 10 academic institutions in the US, Canada, and France; an analysis of 386 patients with CIS of the bladder with or without associated pTa/pT1 disease treated with BCG between 2008 and 2015; a review of the records of 398 non–muscle invasive bladder cancer patients treated between 2001 and 20179-11

BCG UNRESPONSIVENESS

The FDA defines BCG-unresponsive bladder cancer as being at least one of the following3

- Persistent or recurrent CIS alone or with recurrent Ta/T1 disease within 12 months of completion of adequate BCG

- Recurrent high-grade Ta/T1 disease within 6 months of completion of adequate BCG

- T1 high-grade disease at the first evaluation following an induction course of BCG

Radical cystectomy is currently recommended as a preferred treatment option for BCG unresponsiveness12,13

Patient-Reported BCG Experience in a Qualitative Interview and Survey14

- Study design: This cross-sectional study included patients with HR-NMIBC who received BCG treatment in the prior 3 years. The study was conducted in 2 phases: 1) qualitative interviews with 32 patients in the United States (US), France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (UK), and 2) a qualitative survey of 150 patients in the US

- Fifty-six percent of patients (n=18) cited the efficacy of BCG as the greatest treatment benefit

- Most patients experienced AEs during administration; however, patients who reported no pain were highly satisfied with treatment

- Two of the most common side effects reported by patients were burning/painful urination (59%, n=89) and urinary frequency (45%, n=68)

Study Limitations14

- Self-reported clinical and treatment-related variables and timing of experience

- Convenience sampling may have reduced socioeconomic variability and underrepresented patients with the most severe comorbidities and disabilities

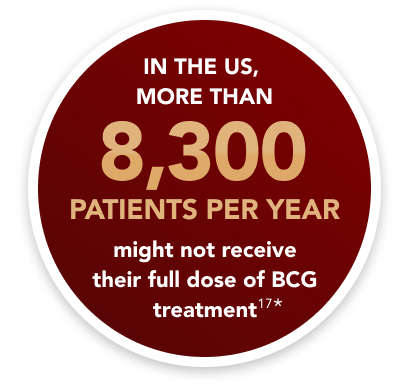

BCG SHORTAGES HAVE LED TO PATIENT PRIORITIZATION, DOSE REDUCTIONS, AND RATIONING15-17

- A shortage beginning in 2012 necessitated the use of alternative dosing and treatment considerations for patients with NMIBC17

- According to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), in the event of a shortage, BCG should be prioritized for high-risk induction patients12

- Intravesical chemotherapy may be used as an alternative to BCG12

- The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN® provides recommendations for dose splitting/patient prioritization12

*Based on supply and demand projections for 2022, there was a shortage of 150,000 BCG vials. This shortage would prevent more than 8,300 patients from receiving their full annual dose of treatment.17

Nonsurgical treatments post-BCG include systemic immunotherapy, BCG rescue, and other intravesical fluid instillations.18

*Based on supply and demand projections for 2022, there was a shortage of 150,000 BCG vials. This shortage would prevent more than 8,300 patients from receiving their full annual dose of treatment.17

References:

Holzbeierlein JM, Bixler BR, Buckley DI, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline: 2024 amendment. J Urol. 2024;211(4):533-538. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000003846

Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, David Crawford E, et al. Randomized intergroup comparison of bacillus calmette-guerin immunotherapy and mitomycin C chemotherapy prophylaxis in superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder a southwest oncology group study. Urol Oncol. 1995;1(3):119-126. doi:10.1016/1078-1439(95)00041-f

BCG-unresponsive nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: developing drugs and biologics for treatment guidance for industry. US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Published August 2024. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/media/101468/download

Packiam VT, Johnson SC, Steinberg GD. Non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer: intravesical treatments beyond Bacille Calmette–Guérin. Cancer. 2017;123(3):390-400. doi:10.1002/cncr.30392

Intravesical administration of therapeutic medication for the treatment of bladder cancer. American Urological Association. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://www.auanet.org/about-us/aua-statements/intravesical-administration-of-therapeutic-medication

TICE BCG [Prescribing Information]. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc.; 2022.

Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163(4):1124-1129.

Böhle A, Jocham D, Bock PR. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus mitomycin C for superficial bladder cancer: a formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on recurrence and toxicity. J Urol. 2003;169(1):90-95. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64043-8

Ritch CR, Velasquez MC, Kwon D, et al. Use and validation of the AUA/SUO risk grouping for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer in a contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2020;203(3):505-511. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000593

Subiela JD, Rodríguez Faba Ó, Aumatell J, et al. Long-term recurrence and progression patterns in a contemporary series of patients with carcinoma in situ of the bladder with or without associated Ta/T1 disease treated with bacillus Calmette-Guérin: implications for risk-adapted follow-up. Eur Urol Focus. 2023;9(2):325-332. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2022.09.007

Taylor J, Kamat AM, Annapureddy D, et al. Oncologic outcomes of sequential intravesical gemcitabine and docetaxel compared with bacillus Calmette-Guérin in patients with bacillus Calmette-Guérin-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. Published online December 17, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2024.12.005

Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Bladder Cancer V7.2024. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. All rights reserved. Accessed March 10, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

Aminoltejari K, Black PC. Radical cystectomy: a review of techniques, developments and controversies.Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(6):3073-3081. doi:10.21037/tau.2020.03.23

Kopenhafer L, Thompson A, Chang J, et al. Patient experience and unmet needs in high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: insights from qualitative interviews and a cross-sectional survey. Urol Onc. 2024;70.e1−70.e10.

Current Drug Shortages. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Updated April 7, 2024. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/drug-shortages-list?page=All

BCG shortage info. American Urological Association. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.auanet.org/about-us/bcg-shortage-info.

Implications of the national BCG drug shortage. End Drug Shortages Alliance. Published February 14, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://info.enddrugshortages.com/External/YCPages/YCYebContent/webcontentpage.aspx?ContentID=68

Bladder cancer. American Cancer Society. Accessed March 8, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/bladder-cancer.html

NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

RC is most commonly performed for high-risk disease that has recurred or persisted after adequate intravesical BCG therapy2

- The risk of progression to MIBC is high in this situation, other salvage treatment options are relatively ineffective, and RC represents a curative intervention2

Many patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC are ineligible for or refuse RC3

- 48% of patients are ineligible for RC

- 38% of patients refuse RC

- Retrospective chart review (January-May 2019) of 2,554 patients with BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, which included patients from various countries, including 600 patients from the US3

CYSTECTOMY IS NOT THE END OF THE BLADDER CANCER JOURNEY

Patients and caregivers need to integrate the burden of urinary diversion into their normal lives and require surveillance post cystectomy.2

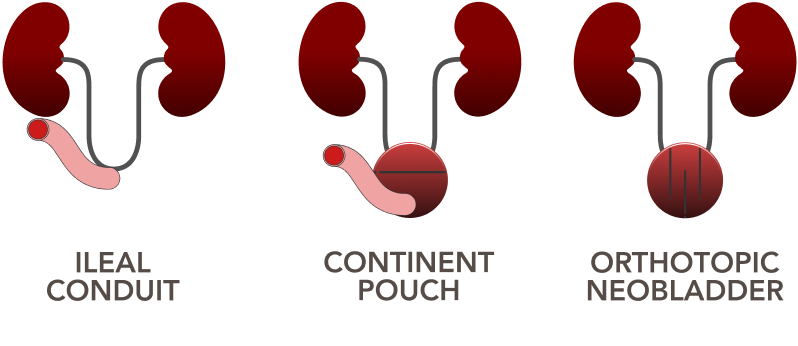

Methods of urinary diversion after radical cystectomy2

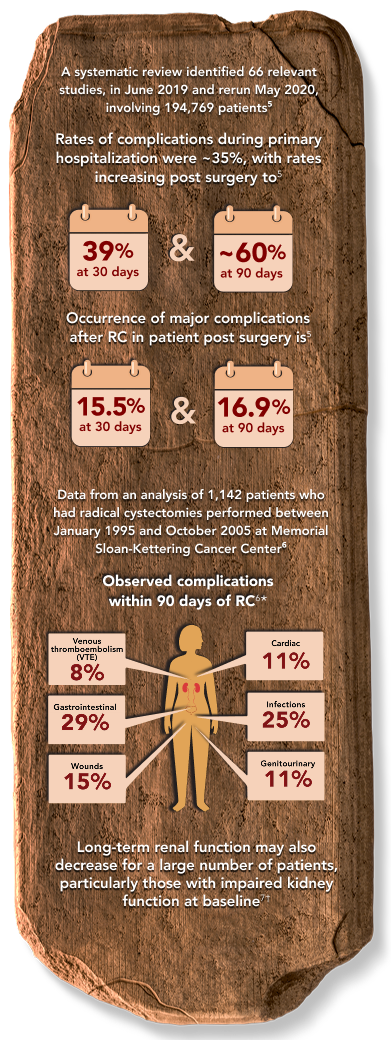

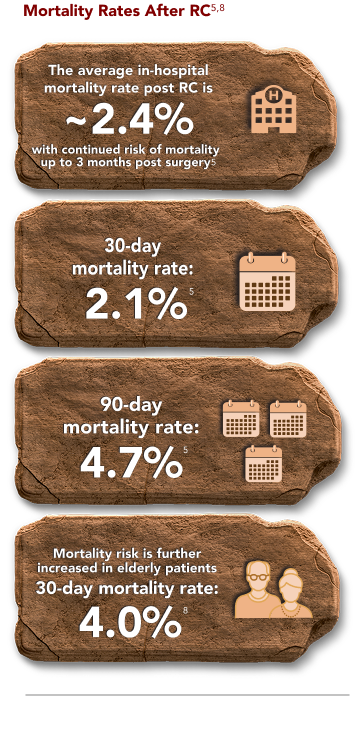

Radical Cystectomy, while appropriate for some patients, is associated with complications4-7

Despite improvements in surgical technique and perioperative care, RC-associated complications continue to be an issue both during surgery and in the months that follow.

RADICAL CYSTECTOMY (RC) CAN HAVE LONG-TERM IMPACT ON PATIENTS9

The majority of patients deal with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

- Patients receiving RC might have treatment-related comorbidities that impact their HRQoL and their daily lives post surgery9

- A study of 30 patients with MIBC who were recruited between 2011 and 2012 was conducted to evaluate the patients’ unmet needs during their illness trajectory9

- Half of patients reported difficulty with postsurgical recovery, and almost half (~47%) reported difficulties related to medical complications9

- During survivorship (~6 months post surgery), ~67% of patients reported difficulties in daily living, ~43% reported changes in sexual function, and ~33% reported emotional distress9

- Treatments requiring patients to travel long distances can also be burdensome, as the distance to care centers has been identified as a reason that patients may be undertreated10

RADICAL CYSTECTOMY (RC) HAS BEEN ASSOCIATED WITH HIGH ECONOMIC BURDENS11

Inpatient costs comprised the majority of post-cystectomy healthcare costs11

- Inpatient costs contributed to 77% of total healthcare costs 6 months after cystectomy

- Physician office visits were a major driver of healthcare costs in the 6 months leading up to cystectomy and formed 81.3% of total healthcare costs

References:

Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Bladder Cancer V7.2024. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. All rights reserved. Accessed March 10, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

Aminoltejari K, Black PC. Radical cystectomy: a review of techniques, developments and controversies.Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(6):3073-3081. doi:10.21037/tau.2020.03.23

Chun S, Broughton E, Gooden K, et al. Reasons for non-surgical management of patients with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Poster presented at: Society of Urologic Oncology; December 2-4, 2020.

Yamada S, Abe T, Sazawa A, et al. Comparative study of postoperative complications after radical cystectomy during the past two decades in Japan: radical cystectomy remains associated with significant postoperative morbidities. Urol Oncol. 2022;40(1):11.e17-11.e25. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.09.005

Maibom SL, Joensen UN, Poulsen AM, Kehlet H, Brasso K, Røder MA. Short term morbidity and mortality following radical cystectomy: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e043266. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043266

Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC, et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. Eur Urol. 2009;55(1):164-174. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.031

Schmidt B, Velaer KN, Thomas IC, et al. Renal morbidity following radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;35:29-36. doi:10.1016/j.euros.2021/11.001

Geiss R, Sebaste L, Valter R, et al. Complications and discharge after radical cystectomy for older patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: the ELCAPA-27 cohort study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(23):6010. doi:10.3390/cancers13236010

Mohamed NE, Chaoprang HP, Hudson S, et al. Muscle invasive bladder cancer: examining survivors’ burden and unmet needs. J Urol. 2014;191(1):48-53. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.062

de Vere White R, Lara Jr PN, Black PC, Evans CP, Dall’Era M. Framing pragmatic strategies to reduce mortality from bladder cancer: an endorsement from the Society of Urologic Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1760-1762. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01731

Tkacz J, Ireland A, Agatep B, Ellis L, Balaji H, Khaki AR. An assessment of the direct and indirect costs of bladder cancer preceding and following a cystectomy: a real-world evidence study. J Med Econ. 2024;27(1):963-971. doi:10.1080/13696998.2024.2382639

NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.